Dodgers’ Freddie Freeman hits walk-off in World Series Game 1

LOS ANGELES — Thirty-six years ago around these parts, Kirk Gibson hobbled out of a trainer’s room, willed one of the most improbable walk-off home runs in baseball history and celebrated the occasion by lifting his right fist into the air. On Friday night, Freddie Freeman raised his bat.

With the bases loaded, two outs and his Los Angeles Dodgers trailing by a run in the 10th inning of one of the most highly anticipated World Series in recent memory, Freeman turned on an inside fastball from Nestor Cortes and watched it fly, sending the Dodgers to a stirring 6-3 victory over the New York Yankees in Game 1.

Bedlam surrounded him. A sold-out Dodger Stadium crowd of 52,394 went into a frenzy. Teammates spilled out of the dugout in uncontrollable glee. And for Freeman — limited all month by a severely sprained right ankle, grinding through the tail end of a bizarre, at-times disheartening season — it was almost as if time stood still. He raised his bat to the sky then began a numbing trot around the bases.

“I felt like nothing,” Freeman said. “Just kind of floating.”

Freeman became the first player in World Series history to hit a walk-off grand slam, a statistic he couldn’t believe. He is the third player in Dodgers history to produce a walk-off home run in the World Series, the last of whom was his teammate, Max Muncy, in 2018.

Most notable, though, was his ties to Gibson, the only other player to send the Dodgers to a walk-off win in the opening game of the World Series. Gibson’s feat, against Oakland Athletics closer Dennis Eckersley, propelled the Dodgers to a title in 1988. The team rallied around his courage. The Dodgers haven’t won a full-season championship since, but they are three wins away from rallying around Freeman for another.

“When you’re 5 years old with your two older brothers and you’re playing whiffle ball in the backyard, those are the scenarios you dream about — two outs, bases loaded in a World Series game,” Freeman said. “For it to actually happen, and get a home run and walk it off to give us a 1-0 lead, that’s as good as it gets right there.”

Often on Friday night, it looked as if the Dodgers wouldn’t break through. They scored only once against Yankees ace Gerrit Cole in the first six innings, doing little to support a highly effective Jack Flaherty despite being presented with a multitude of opportunities.

After Giancarlo Stanton delivered a two-run homer for the Yankees in the sixth, his sixth of this postseason, the Dodgers got a leadoff double from Tommy Edman, bringing up their celebrated top of the lineup. But Shohei Ohtani, Mookie Betts and Freeman were retired in order. The Dodgers had two runners in scoring position with one out in the seventh, but Will Smith and Gavin Lux couldn’t come through.

Walk-Off HRs in World Series G1

Dodgers star Freddie Freeman hit the fifth walk-off homer in Game 1 of a World Series. The teams that won in the four previous instances went on to win the championship.

Ohtani ultimately tied the score in the eighth, doubling off the wall in right field, sprinting to third base when Juan Soto’s throw got away and scoring on Betts’ sacrifice fly. When Jazz Chisholm Jr. manufactured the go-ahead run in the top of the 10th — lining a single, stealing two bases and scoring on a fielder’s choice groundout — the Dodgers came back again.

Lux drew a one-out walk, and Edman followed with a single, bringing up Ohtani and triggering a bizarre decision from Yankees manager Aaron Boone. Cortes, a veteran left-handed starting pitcher who had been recovering from a flexor strain and hadn’t appeared in a game since Sept. 18, was summoned from the bullpen to face Ohtani. On Cortes’ first pitch, Ohtani lofted a fly ball to foul territory in left field. Alex Verdugo made a spectacular lunging catch, but he also rolled over the fence and out of play, prompting both runners to automatically advance. With first base open, the Yankees elected to intentionally walk Betts and set up the left-on-left matchup with Freeman.

Freeman faced Cortes three times earlier this year, when the Dodgers visited Yankee Stadium on June 8. As soon as he saw plate umpire Carlos Torres raise four fingers to signal Betts’ free pass, Freeman started to go through his process. He remembered how Cortes’ fastball had ride to it, and he wanted to look for it on the inner half, partly to stay away from chasing the cutter and slider away. He told himself to stay on top of the pitch.

“I wanted to be on time,” Freeman said, “and I was.”

The ball left Freeman’s bat at 109.2 mph and went 409 feet into the right-field pavilion. A no-doubter.

“I know everybody’s focused on Ohtani, Ohtani, Ohtani,” Cortes said. “We get him out, but Freeman is also a really good hitter. I just couldn’t get the job done today.”

When the World Series concludes, Freeman’s Under Armour cleats will be donated to the Hall of Fame. At 8:38 p.m. PT Friday, they were with him as he vigorously high-fived first-base coach Clayton McCullough, flexed toward the left-field fans on his way to third, got swallowed by bobbing teammates at home plate and sprinted to the backstop to celebrate with his father, Fred Freeman, who was seated nearby.

“I was shocked,” Fred said of his son coming over. “I was so excited and proud of him.”

It was a spur-of-the-moment decision, motivated by all of those days Fred tossed his son batting practice.

“My swing is because of him. My approach is because of him,” Freeman said. “I am who I am because of him.”

The past three months have been a whirlwind for Freeman. His young son, Max, had a scary bout with Guillain-Barré syndrome before making a miraculous recovery, prompting Freeman to be away from the team for 10 days. Freeman then suffered a nondisplaced fracture in his right middle finger. On Sept. 26, the night the Dodgers clinched their 11th division title in 12 years, Freeman rolled his right ankle on a play at first base.

Every day that followed has been a fight.

“He’s doing something that is basically heroic to put himself in a position to even be available,” Dodgers utility man Enrique Hernandez said.

“Freddie’s a competitor, a fighter,” Betts added. “He’s a part of this group, and this group loves each other. Him, like the rest of us, will do whatever it takes to play. It couldn’t happen to a better human being. Freddie goes through so much. He doesn’t complain. He shows up ready to go no matter what.”

Freeman’s ankle reacted poorly when the National League Championship Series shifted to Citi Field in New York last week, so much so that he was out of the lineup for the pennant-clinching Game 6. The Dodgers winning that Sunday, though, ensured Freeman would receive six full days of rest before Game 1 of the World Series. Freeman stayed away from running, instead doing light defensive work, taking batting practice and undergoing lots of treatment.

Along the way, he found a cue that involved, in the words of Dodgers hitting coach Robert Van Scoyoc, “staying planted to the ground so he could rotate and transfer.” Freeman took batting practice Tuesday and continually hit line drives to the area of shortstop. He felt he was in a good place.

When lineups were introduced Friday, it marked the first time he had actually run onto the field to shake hands with teammates who lined up along the third-base line. When he took his first at-bat, he produced a liner down the left-field line that caromed off the fence, rolled past Verdugo and resulted in his first career postseason triple.

Nine innings later, he shocked the world — just like Gibson.

With one exception.

“I played the whole game,” Freeman said.

ESPN’s Jeff Passan, Jesse Rogers and Jorge Castillo contributed to this report.

World Series: Dodgers eye sweep with, yes, a bullpen game

NEW YORK — For decades, the Los Angeles Dodgers were known for superstar starting pitchers.

These pitchers remain so indelible that surnames largely suffice: Koufax, Drysdale, Valenzuela, Hershiser, Kershaw, all of whom made World Series starts for championship Dodgers teams.

The Dodgers’ 4-2 win in Game 3 of the 2024 World Series on Monday put them on the cusp of another championship, with a historically insurmountable three games to none headlock on the New York Yankees. L.A. can clinch in Game 4 on Tuesday — traditionally a tremendous opportunity in the career of an ambitious starting pitcher.

The Dodgers’ Game 4 starter? In the aftermath of Game 3, the answer to that question remained: Relief pitcher TBD. But we do know it’s going to be a bullpen game to perhaps win the World Series.

“That would be fun, obviously, to go out and contribute something like that,” Dodgers reliever Daniel Hudson said. “I’m not sure what we’re going to do, but we’ll go out there and get three, four or five outs and get the ball to the next guy.”

This postseason has seen the prominence of the 2024 version of bullpen deployment evolve into something new.

In: Relievers used at any point in the game — including the beginning, as the Dodgers plan to do in Game 4.

Out: Preconceived roles. The fewer of them you have, the better.

“The guys we have down there,” righty Ryan Brasier said, “we compete, and we’re a super-close-knit group. We have fun, but at the same time, when it’s time to lock in, everybody gets on the same end of the rope and pulls.”

This is not how the Dodgers drew it up last winter, when they signed Yoshinobu Yamamoto to a massive deal, augmented him with a slightly-less-massive deal for Tyler Glasnow and brought back Clayton Kershaw. Add in returning starters, including a number of young arms, injury returnees such as Game 3 winner Walker Buehler, toss in trade deadline pickup Jack Flaherty, and you’ve got a starting pitcher bonanza.

Instead, the rotation was beset with so many maladies the Dodgers have had to lean hard on a bullpen that itself seems to have no clear pecking order. The improvisational nature of L.A.’s pitching plan was known from the outset this October. The bullpen roles for the Dodgers were always fluid, but that dynamic was compounded by the shortage of starters. It’s been all up for grabs.

“There are five or six guys that have got a save maybe in this season,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said at the start of the playoffs. “I feel very comfortable. They’ve all pitched in leverage, whether it be the fifth, the sixth, the seventh or the ninth. Whatever pitcher I feel is best in that particular part of the game, part of the lineup, that’s who I’m going to use.”

Ohtani, unlocked!

In his first postseason, Shohei Ohtani has shed his stoic persona. Alden Gonzalez »

In his first postseason, Shohei Ohtani has shed his stoic persona. Alden Gonzalez »

It’s turned out to be a feature, not a bug. Try to imagine the Dodgers’ relief staff as a 19th-century, Old Hoss Radbourn-style of pitcher who pitched every game. That pitcher has a 3.16 ERA over 68 1/3 innings, 13 holds, four saves and no blown saves. Dodgers starters — including a few openers — have a 4.76 ERA in 11⅔ fewer innings.

Roberts and pitching coach Mark Prior have massaged the plan with remarkable acuity.

Consider Blake Treinen, whose stuff has been reminiscent of his best years, when he was one of the more unassailable relievers in the game. In the past, when managers have had a reliever throwing the way Treinen has been, they might stick him in the back of the bullpen and assign him the last three, four or five outs.

Not Treinen. He’s had a two-inning save, been pulled after giving up a couple of hits in the ninth, and has gotten outs in the sixth and seventh innings. Brasier has pitched in the first (twice), fourth, sixth and eighth. You can see any reliever at any time if the leverage is right and the matchup against a certain sector of the opposing lineup can be exploited.

The deeper we’ve gotten into October, the deeper Roberts has been willing to let his recovering starters work. Thus, Yamamoto and Buehler have given him not just efficiency but more length than was anticipated when the series began. This, in turn, reserves resources for things like, say, a bullpen elimination game.

“I’d put our bullpen up with any bullpen that I’ve ever been on and any bullpen I’ve ever seen,” screwballer Brent Honeywell said. Honeywell, who was one pitcher more or less ruled out to open Game 4, nevertheless might get a shot during what the Dodgers hope will be the last game of the season. “I want to win, and if that’s how we’ve got to do it, that’s how we’ve got to do it.”

The Dodgers are not the only team we’ve seen do this during the postseason. And playoff bullpen games have been around since at least 2019, in the form we know them now, but what we’ve seen this October has felt different. It’s not bullpenning as last resort, it’s bullpenning because you can’t score on our freaking relievers, no matter who they are so, maybe, just maybe, we’re glad we have to do it this way.

The potential pitfall is overexposing your relievers to the same group of hitters too many times over a long series. Roberts is all too aware of that challenge.

From the World Series to Cooperstown?

How many future Hall of Famers are in the 2024 World Series — and is it the most ever?

How many future Hall of Famers are in the 2024 World Series — and is it the most ever?

![]() David Schoenfield »

David Schoenfield »

“Taking a long and short view of the series kind of weighs into my decision-making,” Roberts said. “It’s a constant kind of weaving in and out. But my pitching coaches do a great job of helping me to kind of sift through it.”

Research done on this topic has suggested this can be a problem, but here’s the thing: This is arguably a bigger problem for the traditional setup/setup/closer model of playoff bullpen management than what the Dodgers have been doing. Sure, there is a hierarchy in every bullpen, even this one, and those relievers are going to see the same hitters in a long series. (Though this series might not be a long one, after all.) But the Dodgers are mitigating that by coming at their opponents with so many different arms in so many different circumstances.

That’s how it scans now, though, because it’s been working. The Dodgers will attempt the ultimate proof-of-concept by rolling out a parade of relievers Tuesday. If it works one more time, the reward will be, well, a parade.

Meanwhile, teams with rock-solid rotations (Philadelphia, Kansas City) and star closers (Cleveland, Milwaukee) have fallen by the wayside. The Dodgers, the team that can buy as much certainty as can possibly exist on a baseball roster, are one win from the ultimate prize, in large part because of how they’ve embraced their bullpen.

Going into Game 4, you might think there’s a little lobbying among the relief group to be the last guy out there. After all, the last-out pitcher of every World Series clincher achieves a measure of instant immortality.

But there is no such lobbying. Not from these Dodgers.

“Nobody here has any kind of ego,” Brasier said. “It’s just when the phone rings, everybody’s ready.”

News

Breaking: An executive order prohibiting transgender people from playing women’s sports is about to be signed by Donald Trump.

BREAKING: Donald Trump Set To Sign Executive Order Banning Transgenders From Participating In Women’s Sports On February 5, 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order titled “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports,” which prohibits transgender girls and women from…

Regarding Donald Trump’s intentions to attend Super Bowl 59, Travis Kelce expresses his feelings rather clearly. tt

Travis Kelce Makes His Feelings Very Clear On Donald Trump’s Plans To Attend Super Bowl 59 It looks like Travis Kelce is taking a diplomatic and professional approach, focusing on the magnitude of the Super Bowl rather than any political…

With a massive trade proposal, the Phoenix Suns set the NBA on fire by trading superstar Kevin Durant to a Western Conference heavyweight. tt

Phoenix Suns Set The NBA On Fireworks By Dealing Superstar Kevin Durant To Western Conference Heavyweight In Massive Trade Proposal That trade proposal is definitely a blockbuster and could shake up the Western Conference in a huge way. If the…

BREAKING: Buffalo Bills All-Pro Superstar Makes Shocking Retirement Announcement After Team’s Heartbreaking Playoff Loss To Chiefs. tt

BREAKING: Buffalo Bills All-Pro Superstar Makes Shocking Retirement Announcement After Team’s Heartbreaking Playoff Loss To Chiefs Buffalo Bills helmet (Photo by Patrick Smith/Getty Images) Former Buffalo Bills star safety Micah Hyde is walking away from the game after an 11-yer career in…

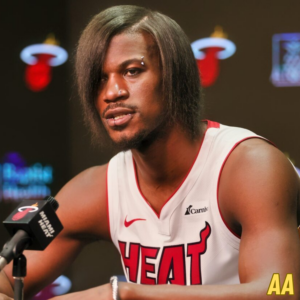

Jimmy Butler of the Miami Heat was acquired by the Dallas Mavericks in a blockbuster trade proposal, once again stunning the NBA. tt

Dallas Mavericks Stun The NBA Again By Acquiring Miami Heat Superstar Jimmy Butler In Blockbuster Trade Proposal As of February 5, 2025, the Dallas Mavericks have not acquired Miami Heat’s All-Star guard Jimmy Butler. However, the team has been active…

Myles Garrett makes a wild, blockbuster trade proposal to join the NFC team with a dynamic quarterback. tt

Myles Garrett Heads To NFC Team With Dynamic QB In Wild Blockbuster Trade Proposal On Monday, February 3, 2025, star defensive end Myles Garrett requested a trade from the Cleveland Browns, expressing his desire to compete for and win a…

End of content

No more pages to load